Chapter 8 Regularized Empirical Risk Minimization

8.1 ill Posed Problems

Let’s start with a simple example: in linear regression, we try to find \(\beta \in \mathcal R^d\) s.t \(\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - <\beta, x_i>_{\mathcal R^d})^2\) is minimized. The solution \(\beta^* = (X^T X)^{-1} X^T Y\) only make sense when \((X^TX)^{-1}\) is invertible, or the optimization problem has a unique solution. The ill posed problems are the situation where there is no unique solution or \((X^TX)^{-1}\) is not invertible (\(d >> n\), not full rank, …).

Ridge regression aims at tackling this problem by adding a “regularizer” to the optimization problem: \(\underset{\beta}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda || \beta ||^2 + \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - <x_i, \beta>)^2\) with \(\beta^* = (X^T X + \lambda I)^{-1} X^T Y\), where higher \(\lambda\) implies more “regular” and lower \(\lambda\) implies lesser “regular”. Naturally, one needs to choose \(\lambda \in (0, \infty)\) to balance between variance and bias.

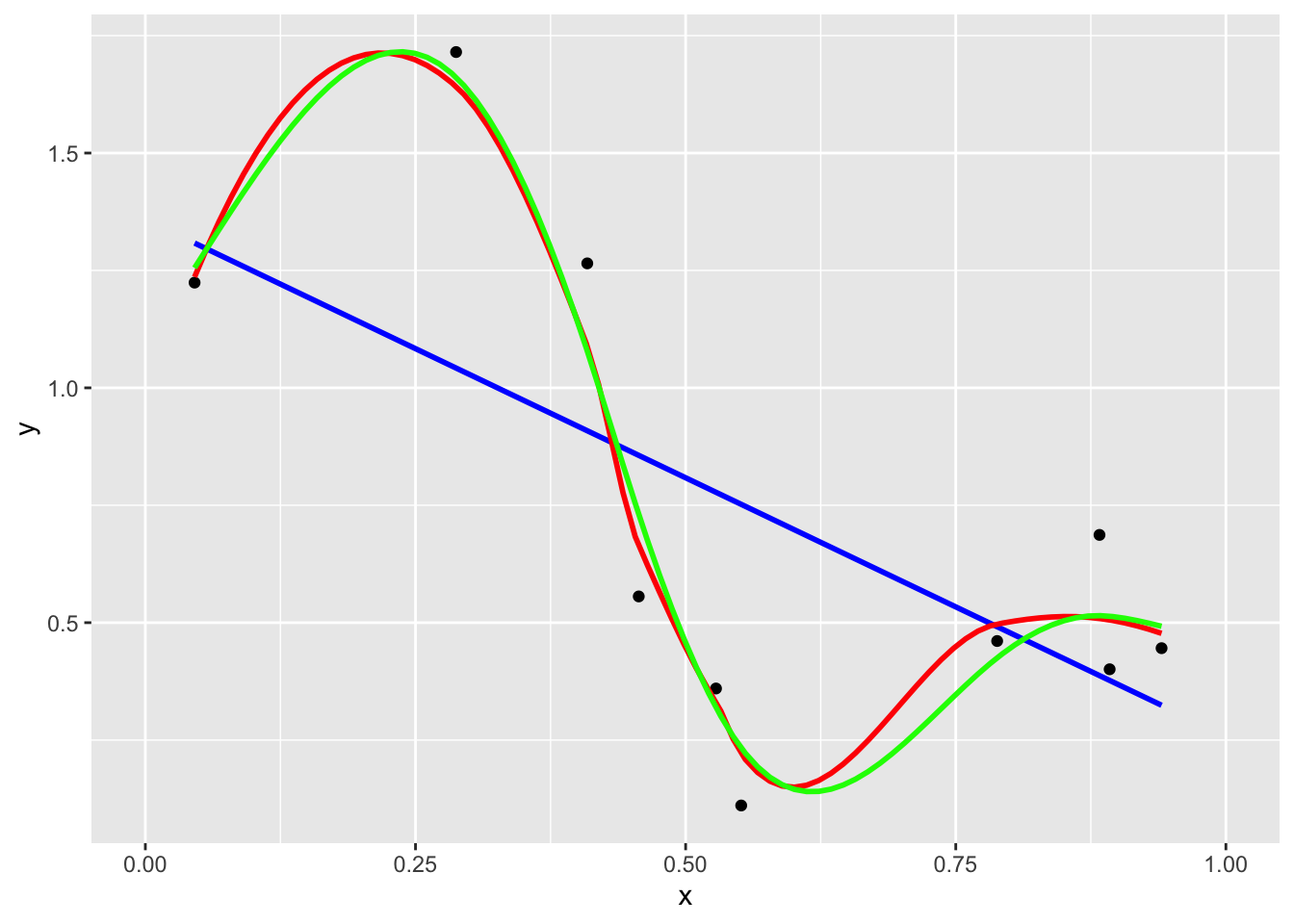

In more generality, suppose we wanted to fit a function \(f\) that explains some observed data (\(f: [0,1] \to \mathcal R\)):

We are trying to solve \(\underset{f \in Z}{\operatorname{min}} \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i) - y_i)^2\). How many functions are close to the observations is the ill posed problem.

The idea in empirical risk minimization is to enforce “regularity” on the functions by adding a regularizer to the empirical risk object function: \(\underset{f \in Z}{\operatorname{min}} \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i) - y_i)^2 + \lambda R(f)\), where \(Z\) is some family of functions for which the objective function makes sense and \(R\) is some regularizer.

Remark. It is important to make sure that the objective function makes sense for elements \(f \in Z\). For example, \(Z\) can not be \(\mathcal L^2(\mathcal R)\), since for an arbitrary \(f \in \mathcal L^2(\mathcal R)\), we can not make sense of \(f(x_i)\).

In any case, after choosing \(Z\) and \(R\), we consider the solution to the regularized empirical risk minimization problem as a regression function for the data. Notice that this approach is a non-parametric approach (\(f \in Z\)).

Q: What types of regularizers we could work with?

A: Later we will consider \(Z = \mathcal H\) (RKHS) and \(R(f) = ||f||^2_\mathcal H\), but for now let us consider an unrelated setting:

Example 8.1 Let \(\mathcal X = [0,1]\) and the data \(0<x_1<\cdots<x_n<1\) with corresponding values \(y_1,\cdots,y_n \in \mathcal R\). Let \(Z\) be the set of functions \(f:[0,1] \to \mathcal R\) s.t \(f(x) = \int_0^x f'(t)dt\), \(\forall x \in (0,1)\) and s.t \(\int_0^1 (f'(x))^2 dx < \infty\). Define \(C_1([0,1])\) as Absolutely Continuous Functions defined on [0,1]. Then, \(C_1([0,1]) \subset Z\) i.e. \(f \in C_1([0,1]) \text{ and } f(0) = 0\Rightarrow f\in Z\).

Now let \(J(f):= \lambda \int_0^1 (f'(x))^2 dx (\text{ Regularization Term}) + \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i) - y_i)^2 (\text{Fidality Term})\). The goal is to:

- Minimize \(J\): \(\underset{f \in Z}{\operatorname{min}} J(f)\).

- Obtain a “first order” condition for optimality.

In search of inspiration, let’s go back to the Euclidean case: \(\underset{x \in \mathcal R^m}{\operatorname{min}} F(x)\).

First order condition: \(\nabla F(x^*) = \vec 0\), that is \(\frac{\partial F}{\partial x_i}(x^*) = 0\), \(\forall i=1,\cdots,m\).

Moreover, if \(x^*\) minimizes \(F\) over the whole \(\mathcal R^m\), it certainly minimizes \(F\) over the line \(\{x^* + tv: t\in \mathcal R\}\). Thus, fix \(v\) and define the function \(\phi_v(t):= F(x^* + tv)\). Then this function has a minimum at \(t=0\), which means that

\[ 0 = \phi'_v(0) = \frac{d}{dt} F(x^* + tv) |_{t=0} = <\nabla F(x^*), v> = \partial_v F(x^*) \]

The optimality condition in \(\mathcal R^m\) is equivalent to the optimality condition fro a collection of functions in \(\mathcal R\).

So, going back to Example 8.1, suppose \(f^*\) solves the problem (it is a minimizer). Pick an arbitrary \(g \in Z\) and consider the function: \(\phi_g(t):= J(f^* + tg)\), \(t \in \mathcal R\). Then \(\phi_g\) has a minimum at \(t=0\) (\(\phi'_g(0) = 0\)). Thus, we have:

\[ \begin{aligned} J(f^* + tg) &= \lambda \int_0^1 (f^{*\prime} + tg')^2 dx + \sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) + tg(x_i) - y_i)^2\\ &= \lambda \int_0^1 (f^{*\prime})^2 dx + 2 \lambda t \int_0^1 f^{*\prime} g' dx + \lambda t^2 \int_0^1 (g')^2 dx + \sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) + tg(x_i) - y_i)^2 \end{aligned} \]

Then, \(0 = \phi'_g(0) = 2 \lambda \int_0^1 f^{*\prime} g' dx + 2\sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) - y_i)g(x_i)\), which means that

\[ \lambda \int_0^1 f^{*\prime} g' dx = -\sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) - y_i)g(x_i) \]

This has to be true \(\forall g \in Z\). These equations are called Euler Lagrange Equations or First Order Optimality Conditions.

Above goes from \(f^*\) to First Order Optimality Conditions. Now consider the opposite situation:

Take \(g=g_1\) where \(g_1(x):= \operatorname{min} \{x,x_1\}\). It follows that \(\lambda \int_0^{x_1} f^{*\prime} dx = -\sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) - y_i)(x_i \wedge x_1)\). As \(\int_0^{x_1} f^{*\prime} dx = f^*(x_1) - f^*(0) = f^*(x_1)\), we have:

\[ \lambda f^*(x_1) = -\sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) - y_i)(x_i \wedge x_1) \]

Doing the same for \(j = 2, \cdots, n\), we obtain the system of equations:

\[ \lambda f^*(x_j) = -\sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) - y_i)(x_i \wedge x_j), ~j = 1, \cdots, n \]

We can solve this system to get the values of \(f^*\) at the points \(x_1, \cdots, x_n\). For the rest of \(f^*\), use linear interpolation for each interval and use a constant after \(x_n\):

To see \(f^*\) is linear in \([0,x_1]\), it is enough to show \((f^*)'' = 0\) in the interval:

Take \(g: [0,1] \to \mathcal R\) s.t \(g(x)=0\), \(\forall x \geq x_1\) and \(g(0) = 0\), \(g \in Z\). Then, we must have \(\int_0^{x_1} (f^*)' g' dx = 0\).

As \(\int_0^{x_1}(f^*)' g' dx = -\int_0^{x_1}(f^*)'' g dx + (f^*)' g |_0^{x_1} = -\int_0^{x_1}(f^*)'' g dx\), \(\forall g\). Thus, we have \((f^*)'' \equiv 0\).To see \(f^*\) is constant in \([x_n, 1]\):

\[ \begin{aligned} J(f)&= \lambda \int_0^1 (f'(x))^2 dx + \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i) - y_i)^2\\ &= \lambda \int_0^{x_n} (f'(x))^2 dx + \lambda \int_{x_n}^1 (f'(x))^2 dx + \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i) - y_i)^2 \end{aligned} \]

As \(J(f)\) has a minimum when \(f'(x) = 0\) at \([x_n, 1]\) and \(f^*\) minimizes \(J(f)\), we have \(f^*\) is constant in \([x_n, 1]\).

8.2 ERM with Kernels

Let \(K\) be a kernel over \(\mathcal X\) and consider \(\mathcal H\) the RKHS associated to \(K\). Consider the problem:

\[ \underset{f \in \mathcal H}{\operatorname{min}}\underset{\text{Regularizer}}{\lambda || f ||_\mathcal H^2} + \underset{\text{Fidality}}{\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - f(x_i))^2} \]

This is actually Ridge Regression in disguise: let \(\psi: \begin{matrix}\mathcal X \to \mathcal H\\x \to K(\cdot, x) \end{matrix}\), \(f \in \mathcal H\), then \(f(x_i) = <f, K(\cdot, x_i)>_\mathcal H = <f, \psi(x_i)>_\mathcal H\), which means we want to solve:

\[ \underset{f \in \mathcal H}{\operatorname{min}}\underset{\text{Regularizer}}{\lambda || f ||_\mathcal H^2} + \underset{\text{Fidality}}{\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - <f, \psi(x_i)>_\mathcal H)^2} \] Here, \(\phi_g(t) = \lambda || f^* + tg||^2_\mathcal H + \sum_{i=1}^n (f^*(x_i) - y_i)^2\), where \(|| f^* + tg||^2_\mathcal H = <f^* + tg, f^* + tg>_\mathcal H = <f^*, f^*>_\mathcal H + 2t<f^*, g>_\mathcal H + t^2 <g,g>_\mathcal H\).

Theorem 8.1 (Representer Theorem) After using the Euler-Lagrange equations with the reproducing property of the kernel, we will deduce:

\[ f^* = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i^* K(\cdot, x_i) \]

Moreover, we can characterize the coefficient completely from \(y_1, \cdots, y_n\) and the matrix \(K = \{K(x_i, x_j)\}\):

\[ \begin{aligned} \underset{a_1, \cdots, a_n}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda || \sum_{j=1}^n a_j K(\cdot, x_j)||^2_\mathcal H &+ \sum_{i=1}^n(\sum_{j=1}^n a_j K(x_i, x_j) - y_i)^2\\ &\Updownarrow\\ \underset{\vec a \in \mathcal R^n}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda <K \vec a, \vec a>_{\mathcal R^n} &+ ||K \vec a - \vec y||^2\\ \end{aligned} \]

8.2.1 Comparison

Example 8.2 Go back to Example 8.1, \(f^*\) coincides with the solution to a problem of the form

\[ \underset{f \in \mathcal H}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda ||f||^2_\mathcal H + \sum_{i=1}^n (f(x_i) - y_i)^2 \]

where \(\mathcal H\) is the RKHS for a well chosen kernel \(K\).

Let \(K: [0,1] \times [0,1] \to \mathcal R\), \(K(x, \tilde x) = x \wedge \tilde x\), by the representer theorem, the solution to the above problem takes the form:

\[ \tilde f := \sum_{i=1}^n a_i^* ~min\{\cdot, x_i\} \]

which coincides with the solution \(f^*\) to \(\underset{f \in Z}{\operatorname{min}} J(f)\) (linear within intervals).

In general, we can consider the optimization problem:

\[ \underset{f \in \mathcal H}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda ||f||^2_\mathcal H + \sum_{i=1}^n G_i(f(x_i)) \]

where \(G: \mathcal R \to \mathcal R\) is general depends on \(y_i\).

For Regression: \(G_i(t) = (t - y_i)^2\) (Usual Square Loss)

But there are reasons to use things like \(G_i(t) = G(t - y_i)\), where \(G\) is the Hubber Loss: \(G(t) = \begin{cases} t^2 & t \in [-1,1]\\ |t| & o.w.\end{cases}\).

For example, to take care of outliers in the labels \(y_i\).For Classification: \(y_i \in \{-1,1\}\)

- \(G_i(t) = \log(\frac{exp(y_i-t)}{1 + exp(y_i-t)})\), problem above is then a regularized (non-parametric) logistic regression.

- \(G_i(t) = max\{0, 1 - ty_i\}\), problem above is then a kernelized soft margin SVM.

Notice that when we solve the above problem for a classification problem, we get \(f^* :\mathcal X \to \mathcal R\), we still need to do

\[ l(x):= \begin{cases} 1 & f^*(x) > 0\\ -1 & f^*(x) < 0 \end{cases} \]- \(G_i(t) = \log(\frac{exp(y_i-t)}{1 + exp(y_i-t)})\), problem above is then a regularized (non-parametric) logistic regression.

Theorem 8.2 (Generalized Representer Theorem) Consider the problem

\[ \underset{f \in \mathcal H}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda ||f||^2_\mathcal H + \sum_{i=1}^n G_i(f(x_i)), \]

the solution is \(f^* = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i^* K(\cdot, x_i)\), where \(a_i^*\) are

\[ \begin{aligned} \underset{\vec a \in \mathcal R^n}{\operatorname{min}} \lambda <K \vec a, \vec a>_{\mathcal R^n} + \sum_{i=1}^n G_i\Big (\sum_{j=1}^n a_j K(x_i, x_j)\Big) \end{aligned} \]

8.3 Regularity

For a given kernel \(K\) over \(\mathcal R^d\), its associated RKHS \(\mathcal H\) is built using the function \(K(\cdot, x)\), \(x \in \mathcal R^d\). Thus, it is to be expected that the regularity of the kernel influences the regularity of the element in \(\mathcal H\). For example, if \(K(\cdot, \cdot)\) has derivatives of all orders, it should not come as a surprise that the element in \(\mathcal H\) have derivatives of all orders (This is the case for the Gaussian Kernel \(K(x, \tilde x) = exp(-\frac{|x - \tilde x|^2}{\sigma^2})\)). Conversely, if the kernel \(K(x, \tilde x)\) is not differentiable (\(K(x, \tilde x) = x \wedge \tilde x\)), the function in \(\mathcal H\) will not be very smooth either.

Also, notice that for the Gaussian Kernel , all functions \(K(\cdot, x)\) have the same amount of regularity, this is because \(K\) is homogeneous, i.e. \(K(x, \tilde x) = h(x - \tilde x)\). In some applications however, it may be useful to have a space of functions \(\mathcal H\) with inhomogeneous regularity.

To change the set of examples of homogeneous kernels, we introduce the following theorem.

Theorem 8.3 (Bochner's Theorem) (A simplified version that doesn’t involve complex random vectors)

Suppose that \(Z\) is a d-dimensional random vector and that its characteristic function: \(h(\vec u):= E[e^{\textbf{i} <Z, \vec u>_{\mathcal R^d}}]\), \(\vec u \in \mathcal R^d\) is real valued. Then, the function \(K: \mathcal R^d \times \mathcal R^d \to \mathcal R\) defined by \(K(x, \tilde x) = h(x - \tilde x)\) is a kernel.

Remark.

Bochner’s Theorem includes a converse statement (If \(K\) is a homogeneous kernel, then \(\exists r.v. Z)\), s.t. the above condition holds) and a more general version for complex valued random vectors.

One way to produce kernel: \(K(x, \tilde x) = E[e^{\textbf{i} <Z, x - \tilde x>}] \underset{M.C.S}{\approx} \frac{1}{N} \sum_{j=1}^n e^{\textbf{i} <z_j, x - \tilde x>}\).

Proof. (Sketch)

Symmetry: \(K(x, \tilde x) = K(\tilde x, x)\).

We would need to show that \(h(\vec u) = h(-\vec u)\). However, if a characteristic function is real values, necessarily it has to be symmetric:

\[ \begin{aligned} E[e^{\textbf{i} <\vec u, Z>}] &= E[cos(<\vec u, Z>) + \textbf{i} ~sin(<\vec u, Z>)]\\ &= E[cos(<\vec u, Z>)]\\ &= E[cos(<-\vec u, Z>)]\\ &= E[e^{\textbf{i} <-\vec u, Z>}] \end{aligned} \]Positive Definiteness:

\[ \begin{aligned} <Kv ,v>_{\mathcal R^d} &= \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n K(x_i, x_j) v_i v_j\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n E[e^{\textbf{i} <x_i - x_j, Z>}] v_i v_j\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n E[e^{\textbf{i} <x_i, Z>} e^{-\textbf{i} <x_i, Z>}] v_i v_j\\ &= E\Big[(\sum_{i=1}^n v_ie^{\textbf{i} <x_i, Z>}) \cdot (\sum_{j=1}^n v_j e^{-\textbf{i} <x_i, Z>}) \Big]\\ &:= E[T \cdot \bar T]\\ &= E[|T|^2]\\ &\underset{\text{conjugate of complex number}}{=}E\Big[|\sum_{j=1}^n v_j e^{\textbf{i} <x_i, Z>}|^2\Big]\\ &\geq 0 \end{aligned} \]

Thanks to this theorem, we can show that the following \(K(x, \tilde x) = h(x - \tilde x)\), \(x, \tilde x \in \mathcal R^d\) are kernels, where

Example 8.3 (Rational Quadratic Family) \[ h(\vec u) = (1 + \frac{|\vec u|^2}{\alpha l^2})^{-\alpha}, ~\alpha, l > 0 \]

When \(\alpha \to \infty\), we recover Gaussian Kernel.

Example 8.4 (Exponential Family) \[ h(\vec u) = exp(-\frac{|\vec u|^\gamma}{l^\gamma}), ~0 < \gamma \leq 2, ~l > 0 \]

When \(\gamma = 2\), we get Gaussian Kernel. Change \(\gamma\), we change the regularity.

Example 8.5 (Matern Family of Kernels) \(\cdots\)

These are all examples of homogeneous kernels. Now let’s make inhomogeneous kernels from homogeneous ones.

Let \(\beta: \mathcal R^d \to \mathcal R^m\) be a non-linear function and let \(\tilde K: \mathcal R^m \times \mathcal R^m \to \mathcal R\) be as kernel. Then, \(K(x, \tilde x):= \tilde K(\beta(x), \beta(\tilde x))\) is a kernel over \(\mathcal R^d\). In particular, if \(\tilde K(z, \tilde z) = h(z - \tilde z)\) is one of the homogeneous kernels we considered before, \(K(x, \tilde x) = h(\beta(x) - \beta(\tilde x))\) is a kernel which in general will not be homogeneous (\(h(\beta(x) - \beta(\tilde x)) \neq h(\beta(\tilde x) - \beta(x))\)).

Example 8.6 Let \(\beta(x): x \in \mathcal R \to (cos(x), sin(x))\). Take \(h(\vec u) = exp(-\frac{|\vec u|^2}{\sigma^2})\), then

\[ \begin{aligned} K(x, \tilde x) &= exp(- \frac{[cos(x) - cos(\tilde x)]^2 + [sin(x) - sin(\tilde x)]^2}{\sigma^2})\\ &= exp(-\frac{4sin^2(\frac{x - \tilde x}{2})}{\sigma^2}) \end{aligned} \]